Laura Lee is in her fifth year at Geneseo. Her major is math. Working on this exhibition has made her realize that there is beauty in death and that these works really bring attention to what we have done to the world and how we must change. She says that it has been an eye-opening experience.

June 1, 2021

The Extinct Birds Project

by Laura Lee

The first bird that “called me by my name” and attracted my attention in Alberto Rey’s Extinct Birds Project, was the Carolina Parakeet with its magnificent green tail feathers. My eyes were instantly attracted to the bright colors and I noticed how the spotlight is on the bird and the background is darkened to bring focus to the bird. Contrasting the green feathers of the body, the eyes of a spectator rest on the head of the depicted and dead Carolina Parakeet. The dark red pulls in the viewer and compels notice of the beak. The beak is decomposing and seems brittle, as if bits and pieces will fall off if someone touches it. Then, one notices the eyes. White. It is heartbreaking to know that these birds will no longer fly high, with their beautiful colors streaking across the sky, and this sorrow was one catalyst that caused Rey to paint this series, as he acknowledged that these birds would no longer be able to fly around his home in Western New York State.

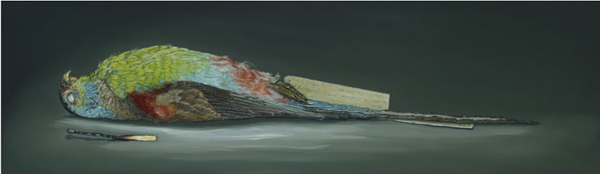

Extinct Birds Project: Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis), 2017, Oil on Panel, 38.25 x 11.7"

The story and life behind each cotton-filled eye of the brightly colored bodies on the table scream for change and attention. My attention was captured as soon as I saw the bright green feathers of the Carolina Parakeet painted by Alberto Rey as part of his Extinct Birds Project. I was immediately brought back to my childhood when I was raising my own birds and I felt a tinge of sadness seeing this bird just left on the table. Each figure, in Rey’s series, that my eyes danced over filled my head with questions of what happened to these lost bird species and how we could have let this loss happen. Alberto Rey addresses these questions and more in this series by sensitively indicating some key issues responding to how human development has impacted the environment of the birds featured in his series, which has resulted in their extinction.

As with so many other extinct species, the story of the species of the extinct Carolina Parakeets began years ago, in the 1800s, when the population of parrots were in the millions before humans began developing landscapes and cutting down trees that were their homes. Humans hunted these birds for their plumage because they were considered highly prized specimens for decorating clothing and these birds were also easy prey for hunters. From what I have read, there was no effort made towards conserving this species. There were not any environmental laws preserving their habitat or conservators making an effort to repopulate their species. Today, we have such environmental preservation efforts, in which institutions, such as The Organization of American States (OAS), are actively trying to protect biodiversity, with stronger environmental laws, which are needed to protect existing birds. Such laws were missing when Carolina parakeets became extinct.

Extinct Birds Project: Paradise Parrot (Psephotus pulcherrimus), 2017, Oils on Wooden Panel, 34 x 10"

Alberto Rey’s Paradise Parrot was the second to grab my attention. The Paradise Parrot looks as if all the vibrant blues, greens, and reds were thrown onto a bird by an enthusiastic painter. The contrast of the dark and light really bring out the vibrancy of the colors. Without the tags in the way, you can really notice the true length of the tail feathers. As you look at Rey’s painted image of the parrot your eyes look towards its head and “face.” In comparison with the Carolina Parakeet, the beak is in better shape but the eyes are the same white and grey, indicative of death and absence. The story of their demise is very similar to that of the Carolina Parakeet. These birds were both desired by collectors for their colorful feathers and their habitats were destroyed by excessive development by humans building homes without attempts at preservation. Another similarity is that they were both last seen around the same time but were considered extinct 70 years later, when sightings of their species ceased.

Extinct Birds Project: Pink-Headed Duck (Rhodonessa caryophyllacea), 2017, Oils on Wooden Panel, 74.75 x 21.25"

Alberto Rey’s Pink-headed Duck is not as colorful as the previous two parrots and the duck is positioned to face away from the viewer, thereby limiting a direct connection. The length of the painting is longer than the previous two, discussed previously. Within all three of these paintings, we notice that there is a common object placed by the head of each bird. A match. This match can be interpreted as a metaphor for finality and the end. The Pink-Headed duck’s end was caused by habitat loss and hunting. There were no laws created to prevent hunting or the collecting of their eggs until it was too late and they were not able to recover. Unlike the Carolina Parakeet and the Paradise Parrot, there was some effort made in trying to breed captive species in zoos but also for private collections. However, the captive birds only lived for a couple of years and their restoration was deemed unsuccessful.

Extinct Birds Project: Passenger Pigeon Egg (Ectopistes migratoria), 2018, Oils on Wooden Panel, 30 x 35.5"

Alberto Rey’s Passenger Pigeon Egg painting is very different in subject from the paintings of the birds previously mentioned because it is an egg. The Passenger Pigeon’s population dropped from billions to zero within 50 years. I questioned how this could have happened and learned that humans hunted them to the point where they could not recover and thus, even though there were some attempts on repopulation, they all failed. Currently, there are projects to revive the legend of the Passenger pigeon through genetic code modification of existing pigeon species, in order to recreate a hybrid that includes the Passenger Pigeon’s generic code, with the ultimate goal of releasing the artificially created species into the wild. This is not a recreation of the Passenger Pigeon which has been forever lost to the world. While the birds are painted on a wooden panel that is longer horizontally than vertically, the dimensions of this egg painting is longer vertically. The egg itself has a small hole on the bottom from where we can assume the contents of it has been drained. The style of the painting is in keeping with that of the Extinct Birds Project works as is the manner in which Rey contrasts light and dark to make the egg look as if there was a spotlight on it. When one looks at this painting, it is possible to imagine what it could never be. It was never born and will be forever frozen in time and potential.

The law that we know now as the Endangered Species Act (1973) only protects the habitats and the animals that are considered to be endangered until they are almost extinct. If such species become extinct, the Act ceases protection of their habitat and all other organisms living within that habitat face the repercussions once all efforts are removed from protecting that area. This act came too late for the birds featured in Alberto Rey’s Extinct Birds Project but through this series of paintings, Rey has been able to give each bird a voice with which to tell us that “we” are responsible for their deaths because “we” did not do enough to protect them. Yet, we do have the ability to protect existing species and through the efforts of the Organization of American States (OAS) and the Art Museum of the Americas (AMA), joint efforts exist to bring attention to the potential we have for saving species, such awakening being the goal of Alberto Rey’s Extinct Birds Project. There is still more work that needs to be done and we will never be able to appreciate the beauty of the lost birds in the wild but perhaps the realization of what has been lost can help to preserve what we still have for future generations.